Global Corridor #3

Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, EU designs (on) Africa's corridors, Genoa's dockworkers threaten blockade, LAPSSET, seeing like a train + radical highway geographies

Dear Readers - welcome to the Global Corridor newsletter. The world is experiencing massive restructuring of its economy, territory and technologies through new global infrastructure projects. Many of the investments in new railways, data-centres, real estate developments, port expansions, special/extractive zones, highways, and more are proceeding through transnational, multi-modal corridors. We are seeing the making of a new global geography at an unprecedented pace and scale. I’ll be providing a round up of some of the most interesting news, stories, data, opinion + academic work that can help us make better sense of this transforming world .

1. Global Infrastructure News Briefing:

A round up of some of the biggest news on global infrastructure projects and emerging implications:

New Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline between Russia and China

Pipelines are always (geo)political and the recently announced pipeline between the two primary rivals of the US is no different. On 2 September 2025, Russia and China signed a legally binding Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to build Power of Siberia 2, a long-awaited pipeline designed to carry natural gas from Russia’s Yamal (West Siberia) fields through Mongolia into northern China. For observers of global energy politics the shifting of flows once destined for Europe southwards to China are important. This is because the pipeline will restructure Eurasia’s energy system, turning Mongolia into a transit state and tying Russia more tightly to China than ever before. The Center for Strategic and International Studies, an American think tank based in D.C. put together a useful briefing of this announcement for those interested in a US perspective.

Power of Siberia 2 adds up to 50 billion cubic meters of export capacity per year to the Russian pipeline network, adding to the 38 billion cubic meters currently shipped through the original Power of Siberia line to China. The Moscow Times set out how this would benefit the two states, adding another significant infrastructural moment in the unfolding Second Cold War:

For Russia, doubling its gas export capacity to China will offset the collapse of its sales to Europe, which have plunged from 157 bcm in 2021 to an expected 39 bcm in 2025. Unlike oil, which Moscow has redirected by sea to Asian markets, gas is largely dependent on pipelines, making new infrastructure essential to increase volumes. Most European countries have stopped purchasing Russian gas. This contributed to a 3.2% year-on-year decline in Russia’s natural gas output to 334.8 bcm in the first half of 2025, following the end of Ukrainian gas transit from Russia to Europe. Energy analyst Sergei Vakulenko estimated that the Power of Siberia 2 could bring in rent between $2.5 billion to $4.3 billion per year. “That’s a far cry from the $20 billion per annum in rent lost from the gas trade with Europe, but still a significant amount,” he said in a 2023 article for Carnegie Politika.For Beijing, expanded Russian gas deliveries can act as a buffer against potential supply shocks stemming from instability in the Middle East or tensions with the West.

EU’s Global Gateway African corridor move

Not to be outdone by China’s attempt to reshape the infrastructure corridors of Africa, and more recent US moves on the Lobito Corridor the European Union’s ‘Joint Research Centre’ has recently published its own ideas of how the continent can be logistically transformed. The report argues that these plans have been developed ‘aiming to strengthen transport and trade efficiency, reduce the carbon footprint and protect biodiversity, enhance digitalisation, improve accessibility, unlock productive areas and support value chains.’ It’s a lot of promises that seem to reflect a new era in which development has been subsumed into an infrastructural logic as well as a new scramble for Africa and its rare earth minerals.

As Alexandra Gerasimcikova and Paul Okumu have previously argued in Africa is a Country the EU’s motives may not be entirely altruistic:

To put it bluntly, Global Gateway is about persuading countries in the Global South to take up loans for projects that they do not need, for supposed benefits that they will not have. All of this conveniently allows the European countries to perpetuate centuries-old strategies rooted in exploitation, as well as to avoid reforms around debt to trade justice that would genuinely free up resources for the Global South countries.

Genoa’s dockworkers “If They Block the Flotilla, We Block Everything!”

The world of logistics and infrastructure operations is supposed to be seamless but the power of workers and communities to blockade and disrupt these flows and circulations remains a key tool of resistance to injustice, whether environmental, economic, or more recently against genocide. As the Global Sumud Flotilla (which you can follow on this tracking software) heads toward the territory with the aim of delivering humanitarian assistance dockworkers in Genoa have threatened to blockade all shipments to Israel if authorities attempt to stop its journey (as they have previously done).

As Left Voice reported, in their statement, the Unione Sindacale di Base, a syndicate comprised of smaller grassroots unions, announced:

Workers can play a decisive role in influencing the outcome of the situation and embody a widespread sentiment in support of this courageous initiative. By blocking ships and aircraft carrying weapons to war zones, they have earned a fundamental role and are well-placed to broaden their perspective on rearmament policies and the consequences they have on our lives.

As many of us have been repeating these days, we cannot stand by and watch. We are sending word to the Israeli minister that his threats will not stop us and that his words are encouraging us to intensify the initiative.

With Palestine in our hearts, full speed ahead!

If they block the Flotilla, we block everything!

I’ll be watching (and supporting) the progress of the flotilla with much interest, and whether the dockworkers are able to ‘block everything’ if it’s stopped.

The ‘Gaza Riviera Plan’

And staying with Gaza I’ve wrote a piece last week for the Conversation on the Riviera Plan for the Palestinian territory which has caused widespread international outrage. With more details revealed by the Washington Post after coverage earlier in the year it’s not surprising the plan is being aligned to the proposed regional logistical network, the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor given the aim of this troubled initiative to cement a pro-American regional architecture.

Acknowledgment that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza – including from the International Association of Genocide Scholars – is becoming more widespread. Israel’s actions have resulted in death and injury to tens of thousands of Palestinians through military violence. I argued the plan for the redevelopment of Gaza can also be understood within this settler colonial logic of elimination: an urban vision that, in order to be achieved, necessitates the erasure of all that stood before through the expulsion of the population and urbicide of the built environment.

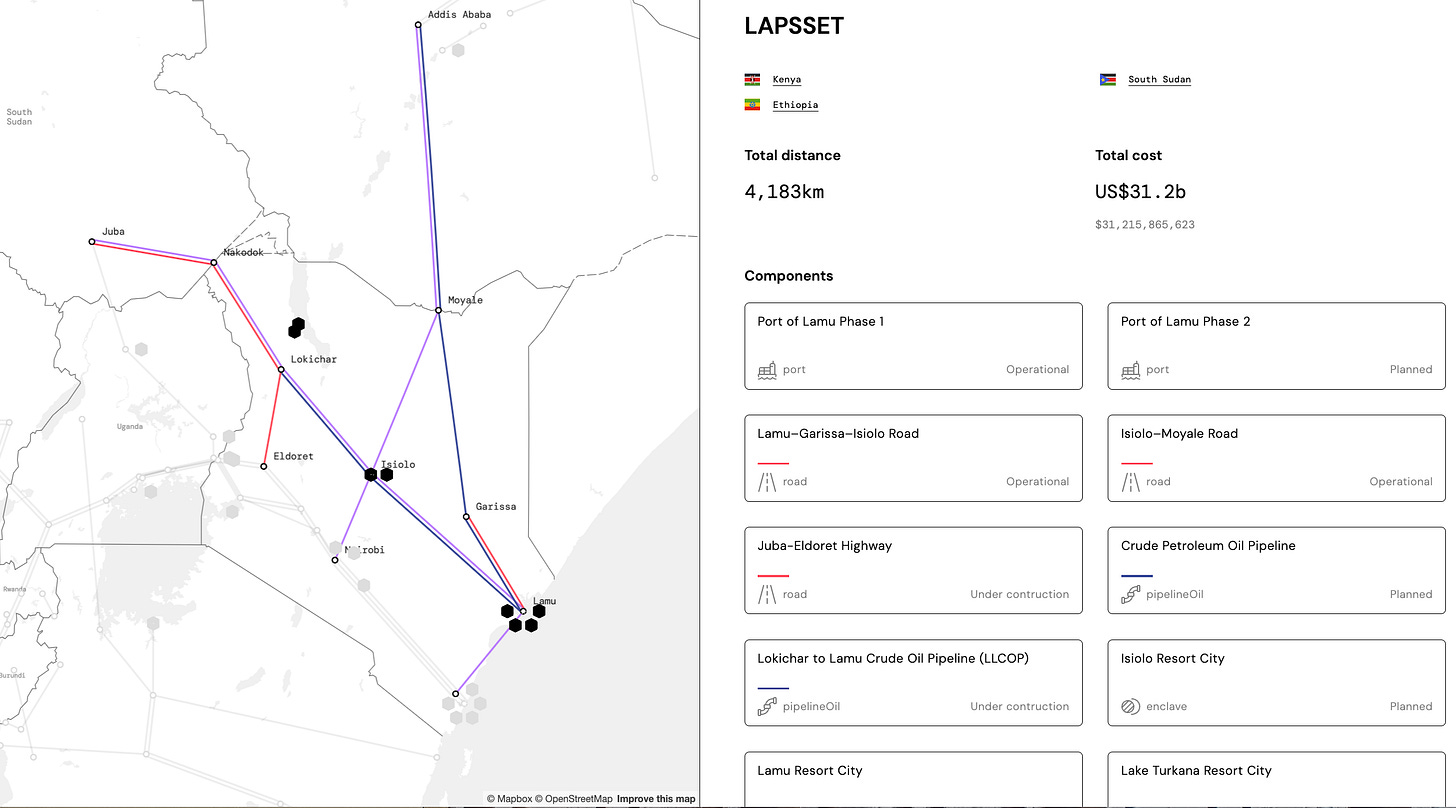

2. Featured Corridor: LAPSSET Corridor

Each newsletter features a more detailed focus on an infrastructure corridor, drawing on the developing Atlas being developed by the Global Corridor project (and due for release in early 2026).

First announced in 2012 with an estimated price tag of $25 billion, LAPSSET has become a highly visible corridor initiative in the region (the initial concept for the project dates back to 1975, it was revived in 2009 and later included in the Kenya Vision 2030).

The key motivations for the project were twofold: Firstly, Kenya’s only major seaport, Mombasa, was apparently struggling under the amounts of cargo it was handling for the region. Through building a new port at Lamu, with space for up to 32 berths, the country could relieve pressure on Mombasa while attracting Ethiopia and South Sudan (both landlocked countries) to Kenya (and onward to the Indian Ocean). It would therefore act as a complimentary trade and economic route to the Northern Corridor and further position Kenya as the global gateway for East Africa.

Second, the corridor was meant to power an economic transformation of the ‘under-developed’ north of Kenya, which as Simba Guleid writes has been historical:

The marginalisation of the northern region dates back to the colonial era, when a combination of a challenging terrain and resistance from local elites to British rule led to its economic neglect

The port vision was to include 32 berths along a 6,000m stretch at Manda Bay. The first three births, which cost $478 million were constructed by the Chinese company, China Communications Construction Company but no more berths have been built. While there was little shipping activity for many years things have started to change in recent months even as the port remains caught in various kinds of politics.

The other infrastructural components were to include a new $3.5 billion SGR railway running 1,700km inland, highways across arid regions that had long been cut off from Nairobi’s attention, and an oil pipeline stretching from South Sudan’s fields. The ripple effects, proponents argued, would be transformative: livestock farmers in Turkana selling to Gulf markets, new resort cities rising and Lamu becoming a ‘modern’ city etc etc.

However, a decade on, the delivery of this vision remains uncertain (and there is some great academic writing that has interrogated its early stages and issues here and here and here). The port has been built but only partially. A handful of roads have opened. The railway and pipeline remain lines on a map. These stalled projects can be partly explained by the price tag for LAPSSET which has hit the limits of Kenya’s fiscal capacity given it faces mounting debt, a weakening shilling, and inflationary pressures that constrain public investment. And external financing has been elusive with promised Chinese investment not always forthcoming and multilateral banks favouring smaller projects.

As well as the economic uncertainties facing the project (in)security has been a clear challenge to its roll out. The project traverses northern Kenya, where cattle rustling, banditry, and clan violence are common. Construction crews and transporters have suffered ambushes, with proximity to Somalia exposing LAPSSET to al-Shabaab. Beyond Kenya, instability is even greater. For instance, South Sudan’s oil field, the pipeline’s intended source, lie in conflict zones where militias have been fighting for control. These threats have raised costs, slow timelines, and deterred investors.

There has also been ongoing local contestation to this corridor. Save Lamu is a community-based organisation founded in 2010. The group emerged in response to some of the corridor’s project including the port and proposed coal power plant (our Global Corridor researcher Wairimu Gathimba has undertaken some fascinating research on this issue). Community members, rightly it seems feared these projects would threaten Lamu’s fragile ecosystems, traditional livelihoods, and UNESCO World Heritage–listed Old Town and have undertaken various kinds of resistance.

3. Featured Image: The Stack

A cargo train passes through central Manchester laden with containers from some of the world’s largest shipping companies with massive new real estate developments providing another kind of stack(ed) background. We tend to think about the ways in which containers reflect global flows but the real estate investments in view are also part of global circulations. Recent months have seen moves by Mayor Andy Burnham to move the main freight centre out of the boundaries of the city to a new custom built logistics centre. Part of the motivation is to limit cargo journeys through central Manchester and free up capacity for passenger trains. However, it’s worth noting that the current freight centre is in Trafford on land that has been earmarked for the new Manchester United stadium.

4. Global Infrastructure on Film

Trains opens with a quote from Franz Kafka: “There is plenty of hope. An infinite amount of hope. But not for us.” These words hang like a dark cloud over this found footage documentary, which creates a collective portrait of people in 20th century Europe, capturing their hopes, desires, dramas, and tragedies. Powerful scenes showing steam locomotives and railroad cars being assembled feel like a celebration of human ingenuity and labor. People dressed in festive attire embark on a rail journey. But these cheerful scenes soon make way for military transport: soldiers being deployed to the frontlines—quickly followed by civilians evacuating, a procession of ragged prisoners-of-war, and amputee soldiers. Times change, the pattern repeats. The archival material in this wordless film evokes an inevitable cycle of delight and destruction, beauty and bitterness. The image of a tangle of railroad tracks and switches raises the inevitable question: Which route will humanity choose?

5. New Academic Papers on Global Infrastructure

Featuring a selection of new academic papers covering various types of scholarship on global infrastructure:

Seeing like a train: the viapolitics of emergency mobilities during Russia’s war against Ukraine by Marta Jaroszewicz, Dovilė Jakniūnaitė, + Peter Adey in Mobilities

“The article investigates the role of trains and railway infrastructure in Ukraine as a critical component of the emergency mobility of Ukraine’s population following the Russian full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. Applying the concept of viapolitics, it explores how the railways became more than just a means of transport during the war, instead symbolising solidarity, struggle, privilege, and hope. The research situates Ukrainian railway mobilities within post-colonial and post-socialist contexts, examining how the infrastructures, rooted in Soviet-era practices, have been repurposed amid military aggression. Drawing on data from news reports, human rights organisations, and personal testimonies, the paper analyses the complex and multifaceted role of rail transport in the war context. The article reveals how emergency mobility, mediated through railways and political action, brings together spatial and temporal dimensions – linking Ukraine’s Soviet past, post-socialist independence, renewed Russian imperialism, and aspirations for a European future. These historical and geopolitical layers intertwine with the population’s self-organisation and resilience, while also colliding within the railway’s diverse vehicular and infrastructural meanings of mobility.”

Towards a radical highway geography: Berlin and the remaking of city logistics in global capitalism by Susanne Soederberg in Environment and Planning A

“Highways are vital to global supply chains, enabling the dominant form of circulating goods inland by truck. Within critical economic geography and related disciplines, however, insufficient attention has been placed on developing a radical highway geography that positions highways within the evolving relationships between global capital, state scales and the labour of moving goods. I fill this silence by applying a historical-geographical materialist lens to Germany’s most congested, costly, and controversial highway – Berlin’s intercity A100 – to explore the entanglements of highways, labour power and the capitalist state within the socio-spatial and temporal dynamics of global capitalism. By following the A100 from the 1950s to the proposed completion of its contentious 16th extension in 2025, I argue that the 16th construction phase is the outcome of continual attempts by the capitalist state – at various scales of intervention – to annihilate space through time. These time–space compressions, which are incomplete, contradictory and contested, facilitate the circulation of commodities – understood here as urban freight and labour power – across space more rapidly and at lower cost, leading not only to a remaking of city logistics but also in the embodied labour of truck drivers, whose working lives increasingly reflect the pressures of accelerated circulation.”

Gatekeeping beyond the state: The mombasa port development program and the emergence of the gatekeeper city by Louis Cyuzuzo in Political Geography

“Since the announcement of Kenya's Vision 2030, infrastructure provision has been cast as a central part of Kenya's development strategy. A key component of this vision is the upgrading of the Port of Mombasa, the largest and busiest port in East Africa, to international logistics standards. Analyzing the implementation of the Mombasa Port Development Program (MPDP), this article argues that it reveals a transformation of the politics of ‘gatekeeping’ - understood as the political contests around the spatial and institutional sites that mediate the circulation of resources between domestic and international political-economic spheres. The controversies surrounding the management of the MPDP reveal how gatekeeping has undergone a process of decentralization, that results in arenas of gatekeeper competition multiplying at the intersection of new institutional and spatial sites of political contestation. The article demonstrates how gatekeeping now increasingly encompasses complex interactions between peripheral city-level actors and international state and non-state actors. Spatially, it emphasizes how gatekeeping contests crystallize around Mombasa's logistics sector, due to the port city's position as a crucial gateway linking the hinterland to global trade networks. This, I argue, is transforming Mombasa into a gatekeeper city understood as an urban space of transboundary logistical entanglements, where a variety of spatial practices encounter, and reconfigure the modalities of gatekeeping.”