Global Corridor #2

China's African port expansion, the end of the Line? Trump's self-named corridor, CPEC, Not Just Roads and Pakistani gateways.

Dear Readers - welcome to the Global Corridor newsletter. The world is experiencing massive restructuring of its economy, territory and technologies through new global infrastructure projects. Many of the investments in new railways, data-centres, real estate developments, port expansions, special/extractive zones, highways, and more are proceeding through massive, transnational, multi-modal corridors. We are seeing the making of a new global geography at an unprecedented pace and scale. I’ll be providing a round up of some of the most interesting news, stories, data, opinion + academic work that can help us make better sense of this transforming world .

1. Global Infrastructure News Briefing:

A round up of some of the biggest news on global infrastructure projects and emerging implications:

More doubts emerge from Saudi Arabia about ‘The Line’

The rather ambitious £800 billion vision to create a corridor city, ‘The Line’ in Saudi Arabia seems to have encountered a new set of challenges that puts its future in further serious doubt. The last few years has been dominated by extensive media attention and promotion of a 170km linear city in the desert that would form the centrepiece of the Saudi Government’s NEOM mega-project and Vision 2030.

More critical coverage has highlighted widespread concern about the human rights implications of the project including labour abuses and serious oppression against the local al-Huwaitat Tribe resisting the displacement of up to 20,000 people. There has also been a heated debate in the architecture profession about the ethics of being involved in ‘The Line’ amid the rush of architects, engineers and consultancies willing to enthusiastically jump aboard the project. Given the almost impossible engineering and finance issues facing ‘The Line’ the plans had already been massively scaled back from the initial announcements to what seemed like a more manageable 2.4 km scheme. Perhaps surprising to some of the project’s sceptics construction has been ongoing over the last year or so with various parts of the project being put into place. However, in recent months there has been further doubt about whether this scaled back version is feasible, with the Wall Street Journal reporting that the wider NEOM project “faced significant challenges, including soaring costs, delays, and unrealistic assumptions in its business plan” and the Middle East Eye, citing rising costs and lower oil prices in prompting “Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF) to ask the consultants to determine whether its plans to build the car-free city are feasible.”

Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP)

In August President Trump announced a new corridor initiative humbly named after himself. The Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP) aims to connect the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic to the rest of Azerbaijan through Armenia through a 99 year exclusive rights deal for the US to develop the route. The TRIPP was announced as part of a developing peace deal between the two states over a contested territory that has its origins in the break up of the USSR and first surfaced in 1988 through the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The corridor has previously been termed (and may be known by everyone except Trump) as the Zangezur corridor and is welcomed by Turkey in its attempts to become the key hub in Eurasian logistical flows. Less likely to be happy with the deal are Iran and Russia, with reduced influence in the region, the bypassing of their territories for different kinds of logistical operations, as well as what will likely be a ramped up US presence in the region over the next decade.

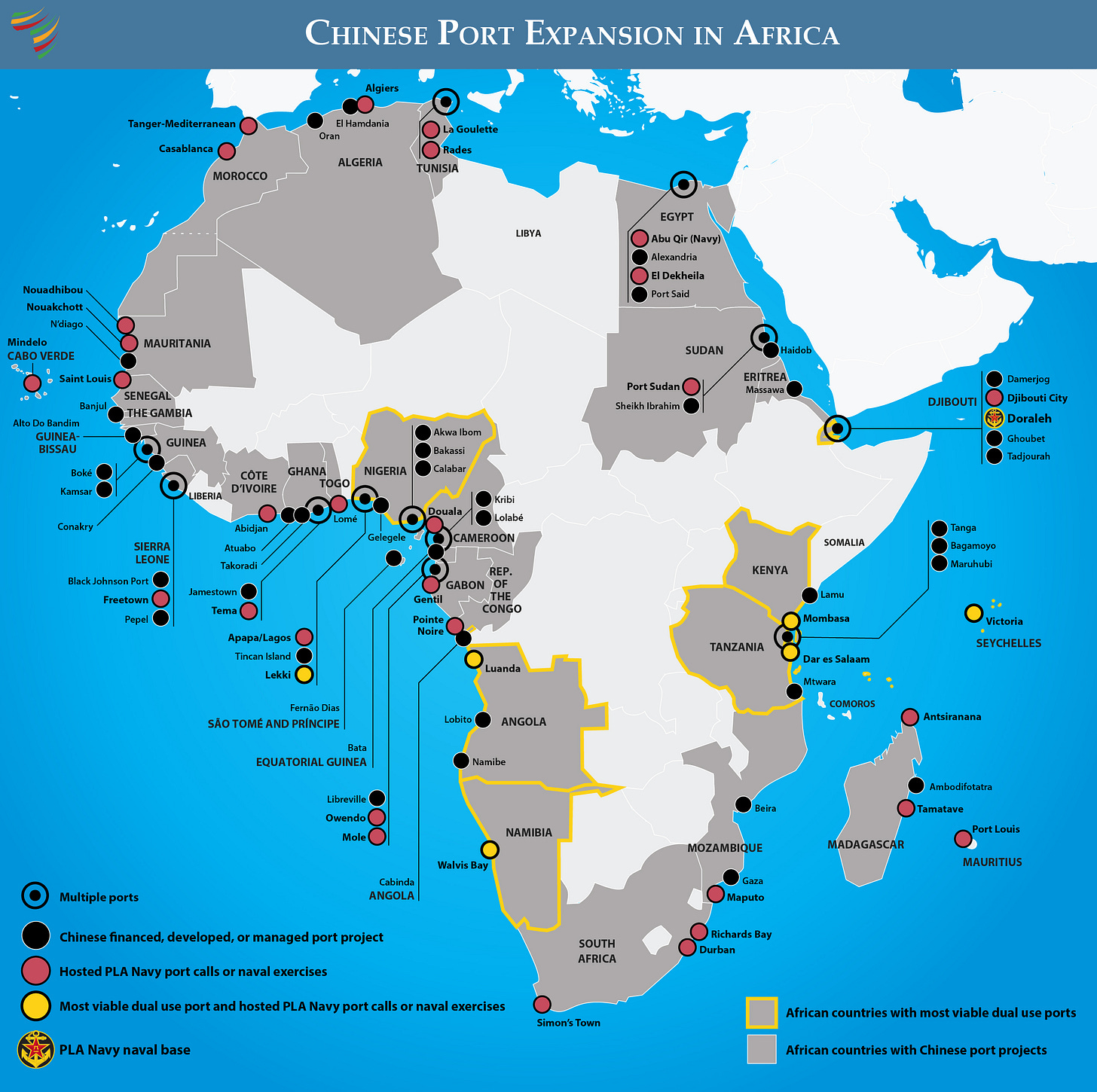

Mapping China’s Strategic Port Development in Africa

A new report released by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (an academic institution within the U.S. Department of Defense) has shown that:

“With a total of 231 commercial ports in Africa, Chinese firms are present in over a third of Africa’s maritime trade hubs. This is a significantly greater presence than anywhere else in the world. By comparison, Latin America and the Caribbean host 10 Chinese-built or operated ports, while Asian countries host 24.”

The report goes on to explore the various kinds of investments into these ports and the leading role of large companies like China Communications Construction Corporation (CCCC) working with specialist firms like China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC) to deliver the massive new investments flowing into Africa’s ports. There is, unsurprisingly given the work has been produced for the U.S. Department of Defence, interesting data demonstrating the ways in which military and commercial uses are crossing over in some strategic sites and the frequency of the PLA Navy calling at various ports across the continent. Given the renewed attention by the US Government on the role of China in Africa’s corridors and logistical networks this report may be a prelude to a range of future civil and military co-operation agreements and investments that will aim to counter this significant presence.

2. Featured Corridor: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Each newsletter features a more detailed focus on an infrastructure corridor, drawing on the developing Atlas being developed by the Global Corridor project (and due for release in early 2026).

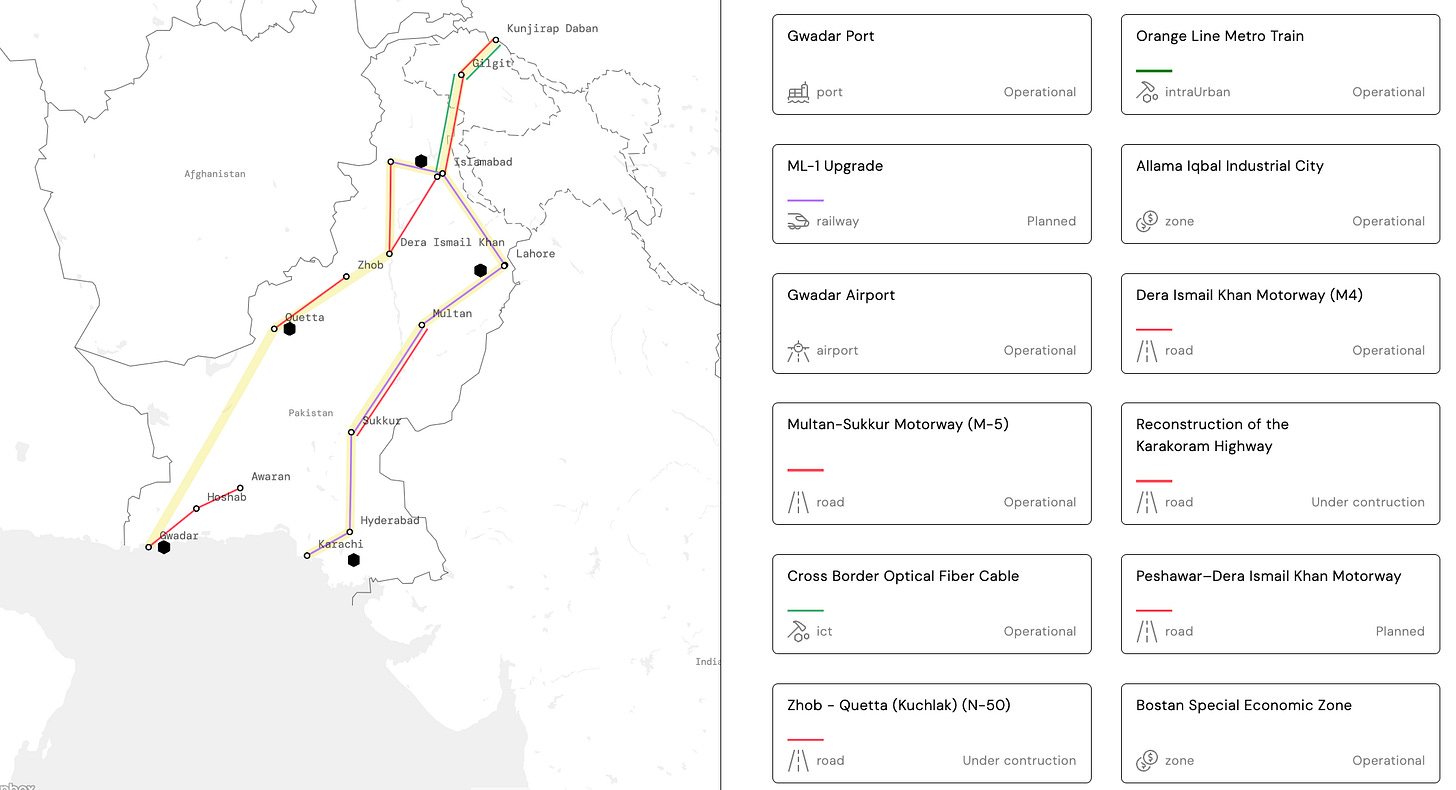

When Pakistan and China launched the CPEC in 2015, politicians in both countries hailed it as"game-changer" shaping a future in which roads, ports, and power plants would transform Pakistan into a hub of global trade and make a serious contribution to GDP and national development. Ten years on, CPEC remains both ambitious and ambiguous. Roads have been built, multiple coal plants have come on stream, and Gwadar Port has risen from a Musharraf era plan to an operational facility. But the promises of industrial growth, foreign investment, and broad-based development remain elusive. At the same time, CPEC has further solidified the “all-weather friendship” (常青友谊) the countries have established in previous decades, sparking increased unease in Washington and alarm in New Delhi (illustrated most recently by the success of Chinese built Pakistan Airforce jets in downing Indian planes)

CPEC is perhaps the flagship corridor of Beijing's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the trillion-dollar program meant to link Asia, Africa, and Europe through infrastructure. For China, Pakistan offered geography: a direct route from its landlocked Xinjiang province in the far West to the Arabian Sea, slashing thousands of miles off maritime trade routes and bypassing the vulnerable Strait of Malacca. For Pakistan, China offered capital: tens of billions in loans, grants, and investments at a moment when Western aid was dwindling and the economy was faltering.

The corridor was not designed from scratch. Gwadar's port development began in the early 2000s. The Karakoram Highway, linking Xinjiang to northern Pakistan, dates to the 1970s but CPEC stitched these pieces into a larger, more ambitious corridor-led vision: a 3,000-kilometer plan cutting across Pakistan's mountains, deserts, and cities. The early years (2015-2020) were defined by a single priority: electricity. Pakistan's cities were crippled by rolling blackouts lasting up to 12 hours a day. Factories stood idle, and public frustration ran high. Chinese companies rushed to build power plants-coal, hydro, wind, and solar-injecting thousands of megawatts into the grid. For instance, the $1.8 billion Sahiwal Coal Plant in Punjab, completed in 2017, became a showcase: two 660 MW units built in record time, supplying power to millions. Yet its legacy is mixed. While it helped ease blackouts, it also locked Pakistan into costly coal imports and long-term contracts guaranteeing high profits to Chinese operators. Similar stories unfolded in other projects including in the Thar Desert towns of Mithi and Islamkot that have experienced displacement and environmental degradation. Other kinds of infrastructure were also constructed primarily, highways which were upgraded and work began on modernizing rail links particularly the Main Line 1 between Karachi and Peshawar. The Karakoram Highway was widened, though landslides and extreme weather underscored the vulnerability of building in such harsh terrain. By 2020, Pakistan could boast new expressways and bridges, but at mounting financial and environmental costs.

The second phase (2020-2025) promised to move beyond power and roads, focusing instead on industrial cooperation and regional trade. Eleven Special Economic Zones (SEZs) were announced, intended to attract manufacturing and create jobs. Yet many remain little more than plans on paper. Investors-both domestic and foreign-have hesitated, deterred by political instability, security concerns, and Pakistan's unpredictable regulatory environment. Gwadar, heralded as the "jewel in the crown," remains controversial. The port has been expanded ($1 billion), a free zone created ($140 million) and a new airport ($240 million) is now operational. Yet talk of it as the ‘new Dubai’ remain some way off. Long standing residents complain of water shortages, electricity cuts, and unemployment. Fishing communities-historically the backbone of Gwadar's economy-say they have been pushed aside as land is taken for development. In 2021, the Gwadar Haq Do Tehreek movement brought thousands into the streets, demanding basic rights in the shadow of these CPEC projects.

CPEC's progress has been shaped by high-level diplomacy. The 2015 visit of President Xi Jinping to Islamabad was historic: 51 agreements worth $46 billion were signed, launching the project with much fanfare. Since then, annual Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) meetings have reviewed progress, often revealing friction. When Prime Minister Imran Khan came to power in 2018, his government initially criticised CPEC as opaque and debt-heavy. But by 2019, faced with a balance-of-payments crisis, Khan softened his stance, traveling to Beijing to reassure China of Pakistan's commitment. In 2023, Pakistan and China reaffirmed their dedication to "CPEC Phase Two," but sceptics noted that the pledges sounded strikingly similar to those made years earlier.Behind the scenes, Pakistan's position has often been weak. Reliant on Chinese loans and facing repeated IMF bailouts, Islamabad has little leverage to renegotiate terms. For Beijing, CPEC is too strategic to abandon; for Pakistan, it is too costly to walk away from.

If Pakistan's politicians have struggled to manage CPEC, its military has embraced it wholeheartedly. For the generals, the corridor is both a strategic asset and an institutional opportunity. In 2016, the army established a Special Security Division (SSD) of more than 15,000 troops to protect Chinese personnel and projects. Senior generals attend CPEC review meetings, often overshadowing civilian ministers. In Gwadar, security checkpoints and military oversight dominate daily life. Critics argue that CPEC has become a militarised development model, where the army acts as both guardian and gatekeeper. Commentators have suggested China prefers to deal with Pakistan's military, which it views as more reliable than shifting civilian governments. For Pakistan, however, the military's central role raises serious democratic questions, most notably whether CPEC is fostering development, or simply reinforcing the dominance of an already powerful institution at the expense of democratic governance.

Like all corridors, CPEC is more than an economic corridor-it is a geopolitical artery with global implications. For China, it aims at reducing reliance on the Strait of Malacca, offering a shorter and potentially safer route for Middle Eastern oil and global trade. Gwadar's location at the mouth of the Persian Gulf places Beijing within striking distance of the world's busiest energy lanes, raising speculation that the port could one day support Chinese naval operations. For Pakistan, CPEC is a strategic hedge. Long isolated in South Asia and locked in rivalry with India, Islamabad sees Beijing as its most dependable partner. The corridor deepens military and diplomatic ties, but at the cost of narrowing Pakistan's foreign policy options and heightening dependence on a single power. Pakistan’s next door neighbour, India certainly views CPEC as a provocation. The corridor runs through Gilgit-Baltistan, part of disputed Kashmir. By financing roads and power plants there, Beijing appears to endorse Pakistan's control, undermining India's claims. New Delhi has boycotted the Belt and Road Initiative altogether, warning that CPEC is part of a broader Chinese strategy of encirclement. The United States has also weighed in, criticizing CPEC as a vehicle for "debt-trap diplomacy" and warning Pakistan that it risks trading one dependency for another. Yet for Islamabad, Chinese investment is one of the few options left as U.S. aid shrinks and IMF loans tighten.

You’ll hear more from our extensive research work with Karachi Urban Lab on many of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects in future months and it has already, given the substantial investment and construction activity become a well researched corridor in academia, including being featured in an excellent special issue in Antipode journal.

3. Featured Image: “Gateways”

The entrance to the Allama Iqbal Industrial City, Pakistan. A new special economic zone developed as part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. A noted hallmark of many new industrial parks or special economic zones seems to be a massive entrance gate that denotes both the securitisation of the land from the outside, and as a symbol of the welcome of new manufacturing and logistical circulations into these spaces. (Image take by J.Silver).

4. Global Infrastructure on Film

NOT JUST ROADS is an ethnographic documentary film directed by Nitin Bathla that narrates the story of a massive urban transformation underway in India. Highways are being constructed at an unprecedented rate of 23 kilometers per day under the Indian government's Bharatmala (‘Garland of Limitless Roads’) program. The program aims to open new territories for the emerging Indian middle class. Currently, the territory is inhabited by villages, working class neighbourhoods, and nomadic herders. It is criss-crossed by native trails and vital ecological commons. This film captures the story of one such highway outside Delhi, from the perspective of human and non-human actors.

Empire of Dust is a 2011 film directed by Bram Van Paesschen. It follows the workers of China Railway Seventh Group (CREC-7), a subsidiary of China Railway Group Limited (CREC), as they construct a road between Kolwezi and Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The film follows two employees of CREC-7, head of logistics Lao Yang and interpreter Eddy, as they struggle to work with the locals due to their cultural differences.

5. New Academic Papers on Global Infrastructure

Featuring a selection of new academic papers covering various types of scholarship on global infrastructure:

The Belt and Road Initiative and Emerging US-China Rivalries in Africa: The Case of the Lobito Corridor by Maria Adele Carrai in Global Policy

Within a geopolitical landscape often framed as a nascent cold war between the United States and China, China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is increasingly pivoting towards the Global South, especially Africa and Latin America. This shift comes amid an increase in new competitive infrastructural initiatives, such as the US-led G7 coalition's Partnership for Global Investments and Infrastructures. This article explores the transformations of the BRI and what was its nascent rival under Biden administration, with a particular focus on the Lobito Corridor, which Trump seems to be supporting too for mineral access. It examines the motivations and strategies of the United States, China, and beneficiary nations, and how dynamics between them may unfold. The study finds that the Lobito Corridor exemplifies how the United States was re-entering African infrastructure markets, challenging China's dominance by targeting critical supply chains. The conclusion posits that this corridor signaled a strategic shift in global infrastructure competition, with the United States leveraging it to reassert influence in Africa, potentially recalibrating China's dominance in critical mineral supply chains.”

Arriving at Airport City Manchester:“Exporting” and “Importing” the Enterprise Zone, Entrepreneurial Governance, and the Geopolitics of Economic Development by Kevin Ward and Alan Wiig in Annals of the American Association of Geographers

“The last four decades have witnessed the emergence of zones of various designations as a means of generating economic development and growth. On the one hand, a considerable amount of recent academic attention has turned to the various experiments with enterprise zones, export processing zones, freeport zones, and special economic zones in rapidly urbanizing areas of Africa and Asia. On the other hand, we see still zones of various stripes used in the United Kingdom and the United States, where their existence dates back to the early 1980s. It is to understandings of the latter that we contribute. Our article takes the example of Airport City Manchester to make three broad contributions to the wider extant academic literature. The first is to underscore the need to be attentive to the relationally interconnected nature of “local” policy experimentation. What we see in the case of the global chronology of zones is their complex, incremental, start–stop–start emergence. The second is that regardless of their spatial demarcation they exist outside of “normal” governance norms and regulations. Each zone is a creature of its geographical-cum-institutional state context. The third point is a reminder of the geopolitical nature of many economic redevelopment strategies, as cities enroll themselves, or others enroll them, in wider global issues.”

TERRITORIALIZING POWER: The Politics of Presidential Projects in Antananarivo, Madagascar by Fanny Voélin, Lars Buur in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

“Large-scale infrastructure projects have become a defining feature of African urbanism. The study of the surge in infrastructure investments has largely been conducted against the backdrop of a purported ‘neoliberal global modernity’ in which cities compete to attract international investments. This article draws on the case of Antananarivo, Madagascar's capital, to contend with this framing and situate large-scale infrastructure projects within national political dynamics. We argue that infrastructural projects are primarily part of presidential strategies for political survival in a highly unstable and competitive political system, and that infrastructure is a key vehicle for consolidating and legitimizing presidential power by territorializing it. We explore how infrastructure projects have been used to channel state resources to key allies of the president while simultaneously anchoring presidential rule in Malagasy history and territory, reshaping state institutions and transforming spatial and political imaginaries of the state in the process. The article thus contributes to the growing literature that links urban policymaking to national politics by proposing a fine-grained account of the intertwined processes of city- and state-making under circumstances of competitive authoritarianism.”